THE NEW MEXICO POETRY ANTHOLOGY 2023 is a multiplicity of voices reflecting the complexity and layers of culture, history, spirituality, and poetic expression that is uniquely Nuevo México. Like the voices filling post office lobbies and general stores, and in the resolanas of our childhood homes of Dixon and Deming, the voices gathered here form a community. No one voice is more important than another. You will find published poets alongside your next-door neighbors, census workers, poets laureate, teachers, senators, high school students, professors, healthcare workers, doctors, and spoken-word artists, all revealing something of themselves that can only be felt through poetry. And, oh, how we have needed poetry to bridge the distance and soothe the isolation created by the pandemic. As we transition from screens back to shared space, may we continue drinking from poetry’s abundant well.

Poetry calls us in the way that grandparents do. It asks us to sit, to eat, to bring ourselves to a kitchen table covered in oilcloth, spilling over with memories and bathed in morning light. If we’re lucky, there’s coffee, bizcochitos, and a heaping platter of stories to nurture our daily lives. As with this anthology, you can stay for hours. Or you can drop in, drink half a cup, and come back tomorrow and the next day.

These voices rise as a canto, singing the joys, sorrows, and praises of individual experiences to form a poetry collective that encompasses the poetic-cultural landscape that is New Mexico. The collection draws on eleven themes that encapsulate the broad expanse and essence of the place we call home—and not merely through speckled windshield observations, but as a witness to people, culture, history, and traditions. The poems are personal interpretations of what it means to be threaded into the cultural fabric of the New Mexican landscape. There are poems that resonate as profound testaments to the sacred ideals of family, community, and identity. Others bestow themselves more to the abstractions and rhythmic cadences of nature and spirituality. They hum along with the water mantra reminding us that in an arid landscape, agua es vida. The collection is an ode and homage to nuestra querencia, our beloved homeland, where we are nurtured, healed, and have a sense of belonging. Here, we honor the generations of stewards, past and present, and we acknowledge that New Mexico exists on the traditional homelands of the 19 pueblos and the Jicarilla and Mescalero Apache peoples, as well as on the Navajo Nation.

Ultimately, we hope this collection speaks for the vastitude and complexity of a New Mexico that is both old and new, a space for community and inclusiveness that poetry itself helps to create.

Levi Romero is the inaugural New Mexico state poet laureate. Michelle Otero is an emerita Albuquerque poet laureate.

SOMEWHERE BETWEEN MILAN AND GALLUP

Hakim Bellamy

Here,

the horizon is open

to interpretation.

An intergalactic dateline

Between New Mexico

and anywhere else.

Where the sun catwalks

the thin line between today

and tomorrow.

A moment of beauty that is also an S.O.S.

A smoke signal. A cry for help.

Begging perfection

to wait.

Damming the inevitable progression

of time.

Barely held together by a steering wheel

enveloped by clenched palms.

White knuckled and painfully aware that even miracles

have an expiration date.

As the moon now illuminates the runway between yesterday

and the rest of our lives,

she takes her rightful place at the new center

of the universe.

The us

we perpetually aim to find

somewhere out there.

Here,

the horizon is still

open

to imagination.

Hakim Bellamy is the inaugural Albuquerque poet laureate (2012–2014) and a national and regional slam poetry champion.

SHIVA

Miguel De La Cruz

That song from the Temptations

Always brings me back

To a charcoal smell, enveloping the air

Just like when my tío passed away

Las risas vienen desde el columpio

I could see, sus amigos gathered around his lowrider truck

—Mira, we are all together just like in high school

—¡cómo estaba loco!

His beat-up keychain was resting on the table

—I love you guys!

—It’s going to be fine

—He was such a good wrestler! District finalist!

—¿Te acuerdas?

A tear hides on the ground

—¡Sí! We are getting old

—Take care, you guys!

—Mija, don’t sell the truck, your daddy really loved his truck

—¡Qué bonito te dejaron el pelo!

—I really like those shoes!

The silver key chain plays with my primo’s hands

—Tell me if you guys need something, just call me!

—Don’t be terco like your father

—También tú eh!

—¡Nos vemos!

That song “Just My Imagination”

Pulls the cables of my heart

It reminds me of that city

The one with a star tattooed on her breast.

Miguel De La Cruz, who calls himself a “border Chicano,” has lived along the U.S.–Mexico border in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico; El Paso, Texas; and Las Cruces.

SONGS OF THE BURIED ONES

Andrea Broyles

breaking through the ground the undead call me

under the strawberry moon

or yellow sun

over the Sangres or the Jemez

the ancient ones,

always singing

from the past and to the future

in front and behind

falling on old deaf ears—

or ears full of noise

silent songs under our feet

can we hop on one leg and shake it loose?

and who are we?

who awakens them

from under this spinning earth?

Andrea Broyles is a visual artist and writer living in Santa Fe.

MOVEMENT

Coral Dawn Bernal

If you are the bird of day

I am the bird’s sleek feathers

If you are sunset’s fire

I am mesa’s golden edges

If you are a well-crafted dreamcatcher

I am the silver sinew that binds it

If you are water’s ripples

I am a stone beneath them

If you are brown skin and soul

I am pure bone and flesh

If you are rainbow waves

I am black-printed fish

If you are a rising sun

I am dawn’s first kiss

If you are still, silent air

I am a raging wind

If you are rushing bodies

I am blood of sin

If you are a spider’s gray web

I am the place where it lives

If you are a long-felt itch

I am the place where it is

If you are shards of pottery

I am the painted mica bits

If you are stacked bricks of earth

I am that structure’s shadow

If you are an onyx hole

I am a rattle-shaped end

If you are electrical wiring

I am clouds shooting lightning

If you are cups of light

I am spoonfuls of velocity

If you are the moon signs

I am reflective outlines

If you are fresh-cut cedar

I am the dried-away smoke

If you are the sweet oak

I am the roots of milk

If you are the last sight

I am the first kill

If you are a poet’s paper

I am the black flowing ink.

Coral Dawn Bernal (1987–2020), “Red Coral Flower,” was a Taos Pueblo poet, Indigenous activist, and artist.

JADE MOTHER

Priyanka Kumar

In the summer, you eye a river

the way you’d tail a breeze.

In the winter, you trail the water,

the pulse of the ochre desert.

You meander with her glaucous body,

inhaling her raging-blue music,

riveted by the spotted towhees

that cleave to her sinuous breasts.

Back home your own river

is awfully arrow straight—

She’s been harnessed so long,

she has forgotten to meander.

In the Gila, though,

the river herself leads you.

You’ve forgotten how to meander,

but the jade river teaches you.

You don’t need to go anywhere—

Just watch the birds weave around her bank.

Thoreau said the best way to see birds is

to sit down someplace and let them come to you.

One winter I started with the creek

and worked my way up to the river.

I hadn’t been to the Gila in some time, and

I hiked down to Bear Creek as the sun dipped.

A motley flock of birds fled to two junipers—

A surprising flash of red, on inspection, was a

cardinal, pomegranate with a black facemask;

the male’s sharp brown eyes pierced me.

A luminous white-crowned sparrow flew to

the Pinos Altos Mountains, where the creek begins.

Lit up with alpenglow, this pink-and-tan range

skirts the rear end of the Gila Wilderness.

The mountains’ sedimentary layers are ghosts

of deep-sea origins. Now they exhaled

soft gilded pinks and grays, so radiant,

they seemed to glow from within.

Down I went, skirting a honey mesquite as its bold

white thorns snagged my jeans. I flushed a handful of

white-winged doves, more slender and curvy

than the mourning doves in my yard.

With flashy blue rings around orange irises,

the doves have the vanity of flamenco dancers.

Losing my battle with light,

I humbly approached Bear Creek.

A mere cub, who, twenty miles from where it begins,

joins the mother bear that is the Gila River, the creek

murmured as the sun slipped beyond the horizon,

reflecting ten thousand beams of light.

Coral pink rippled into the blue-gray sky.

As I lingered . . .

a lone ruby-crowned kinglet hopped in a bare tree,

solitary but content, like me, to be breathing beauty.

Priyanka Kumar is a Santa Fe-based writer and filmmaker. Her most recent book is Conversations with Birds (Milkweed Editions, 2022).

ODE TO PBULULU (NATIVE WILDPLUM)

Joshua K. Concha

Reaching

through thorny,

brambly branches:

well worth

every scratch

on hand,

nicked beyond

even elbows,

arm skin

scraped:

gatherin

colors from

Summer's

waning

sundowns

drenche

on your

skin too—

Pbululu.

Our happy

reward:

tart, sweet

slightly

bitter,

eaten raw

right off

dusty roads,

(and forewarned

by Elders

to consume)

we would

endure

aching

in our

abdomens

for you—

Pbululu.

In spring

I learned

your name,

as a pale

pink earthy

blossom scent,

softly spoken

contentment

for bees

from you—

Pbululu.

Deep winter

delivers delight

when, in

your presence:

iridescence,

luminous liquid

essence,

you bring

kindness

into my bowl,

humble bear

mush made

fragrant,

pleasant

by you—

Pbululu.

Joshua K. Concha lives on and tends land at Taos Pueblo. He is the current Taos poet laureate.

THE ROADRUNNER

Mary Oertel-Kirschner

She’s preening on the patio,

picking, picking at her chest feathers,

obsessing—or so it seems as I watch from the kitchen window—

about the tiniest detritus lurking in her fluffed-up front.

I study the cleansing ritual with fascination,

feeling it surely must be a sort of preparation, but for what?

Then WHOOSH!

She makes a rapid ascent to the web of old wisteria vines

tangling the trellis.

She inches along, stopping every couple of seconds

to check conditions.

Her beady eyes scan left, then right, until she stops dead still.

I wait motionless behind the glass.

Then WHOOSH again!

She rockets into a raggedy nest I hadn’t noticed before.

She sits there low, immobile,

her long rudder of a tail jutting out like a sleek spear.

Now that I’ve got this Mama in my sight, I feel a tender protectiveness.

I put chunks of raw chicken out early

and it disappears before noon,

though never while I’m watching.

I picture the family cozied up and eating chicken

in that messy nest.

Days pass. I don’t see any action.

I go out to have a closer look and spot two stiff miniatures

dropped down to a pile of dry leaves on the patio.

I pick them up—their weight like feathers—

and tuck their tiny bodies into the sand under a juniper bush.

The nest is abandoned, no Mama around.

It’s only two birds, I tell myself,

but sadness wells up in me.

Mary Oertel-Kirschner is an Albuquerque poet, painter, and fiction writer.

ANIMAS, NEW MEXICO 1945

Carmela Lanza

I am just a girl.

My first memory is opening

my eyes to the dark blue New Mexico sky.

There is light coming through the small window.

I am in the back room

and I can barely smell the wood

burning from the kitchen.

I am in the back room

and it is cold

so I am wrapped in a blanket,

a blanket my grandmother made a long time ago.

My toes feel the holes in the blanket.

I can roll off the bed

and walk to my mother.

I am not a martyr.

I am only two years old

and I want to lick the sunlight

that is shining down on my fat, small hand.

“Aga, Aga,” is all I hear,

Of the agate of the heart,

Of the artery traveling to the heart,

of the love that I am just beginning to

shape into a word, a sound I only speak.

If I could find a pomegranate seed,

it would have the taste of me sealed inside,

a small girl here in Animas, New Mexico,

where the souls of the dead arrive.

One rosary bead at a time,

each one opens a bit like

a tiny red rose,

like a round bead of blood.

No, I am a girl here.

I try to touch the light that is coming in,

that is hitting the soft wood floor.

When I walk on that floor I feel the powder fine dirt under my feet,

from everyone, from the wind bringing in that dirt,

like a dried ocean we all must breathe in,

if I fall everyone can see my sandy brown feet,

what the spider only saw,

what the ant only saw,

what the dung beetle only saw,

now everyone sees,

my dirty feet rubbing against the floor.

When I put my face down to the floor,

I see between the cracks of wood,

I see the bugs

and I breathe in the dirt,

it tastes like rain,

like a river that is so far away from this place,

the river has no memory of being a river,

only wind blowing the dirt in my mouth.

Now I hear the goats outside crying for

their mothers,

“Mamamamamama, Mamamamamama,

Mamamamamama,”

and now I want to cry,

Aga, Aga, Aga,

the dirt on my face tastes like salt,

I cry with the goats

and hope someone finds me soon.

Carmela Lanza has published poetry in two chapbooks and numerous anthologies. She is an associate professor of English at the University of New Mexico-Gallup.

ANCESTORS IN US, WITH US

Venaya Yazzie

Rooted strong—

high desert cedar trees tower like the mesas.

I speak with a green sage tongue

where female words sparkle like water—

like shimmering summer storm clouds,

like the shimmering eyes of brown grandmothers.

Like the purple juniper berries on the trees,

the old language lives atop my fingertip swirls:

adindii, adindii—shining, shining.

Rooted at the foot of Huerfano Mesa,

grandmother prays,

prayed, is praying inside a circle home where her songs and sodizin rise—

like shimmering winter star constellations,

like the shimmering eyes of her brown grandchildren.

Like the mesa clouds of old

female Athabaskan language lives atop my fingertip swirls:

másaní, másaní—grandmother, grandmother.

Matriarch speaks with glittering hands, each finger gripping the femme voice,

curving lines

where female words dance vertical—

like the shimmering waters of the Animas

like the shimmering overflowing arroyos at Creation.

Like the river flows,

Matriarch sits and pours her migration

and old language lives atop my ridged fingertips:

nihi zaad, nihi zaad, our voice, our voice.

Venaya Yazzie is Diné/Hopi, from northwestern New Mexico’s San Juan Valley.

HOW TO SELL A WEAVING

Laura Tohe

Trading post day and Masaní

gathers lightning and mountains

she pulled from the sky and

wove onto parallel lines

for she is part geometrician,

part coyote.

She buries her treasure

in the cornfield

damp from desert rains

still fresh from the memory

of the loom before she will walk

to the trading post and get only

half for the weight of mountains and lightning,

half for woolly clouds spun into horizontal lines on her lap,

half for her creation laid down one line at a time.

But in her dwells an old Indian trick:

she shakes off the sand and retains the dampness

for the scale from which the trader will pay her

full for the weight of mountains and lightning,

full for woolly clouds spun into horizontal lines on her lap,

full for her creation laid down one line at a time.

Laura Tohe is the current Navajo Nation poet laureate, of the Sleepy Rock People clan and born for the Bitter Water People clan.

READ THE POETRY OF NEW MEXICO

READ THE POETRY OF NEW MEXICO

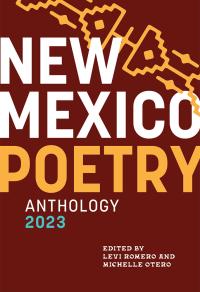

New Mexico Poetry Anthology 2023, edited by Levi Romero and Michelle Otero, features 227 poems by New Mexico poets from around the state. The anthology, published by Museum of New Mexico Press, in association with the New Mexico State Library Poetry Center, is available from local booksellers and online at nmmag.us/poetry.